Killybegs has many stories; stories of pirates, priests and planters; stories that have shaped lives near and far; famous stories and half-forgotten stories.

The little church of St. Catherine of Alexandria has stood on a shoulder overlooking Killybegs harbour since at least the fifteenth century. Just a few yards away, the Well dedicated to the Egyptian saint continues as a place of daily pilgrimage. But the church and its surrounding graveyard – unused and uncared for – has largely slipped from community memory so that many barely know of its existence.

Here we take a look at the church’s relevance to the history of Killybegs and the surrounding area, to where the remains sit within the modern community.

Text and historical information taken from St. Catherine’s Church & Graveyard and the Medieval Town of Killybegs, Published in 2008 by Killybegs Community Response Scheme

People have lived in the area of Killybegs since prehistoric times and evidence of their existence can be found at sites all around the town (see https://webgis.archaeology.ie/historicenvironment/).

Situated at the mouth of a fjord in the bay of Donegal, Killybegs is a natural settling point for access to fishing waters and fertile soils at the foot of Donegal’s more rugged landscapes.

It is believed Christianity came to Killybegs before the 6th century, when St. Colmcille was active along this south-west Donegal coastline.

Killybegs came under the control of the Scottish Mc Sweeney clan from around the 14th century. They gave their name to the bay nearby. It is from this period Killybegs begins to develop and the Church of St. Catherine is constructed.

The map shows the position of the church within the settlement area. Situated on the water’s edge, St. Catherine’s church would have been central to the early settlement and a pilgrimage point for the surrounding area.

St. Catherine’s Church is located to the south of Killybegs on the west side of Killybegs Harbour. Its position is probably located in the area adjacent to the medieval town of Killybegs.

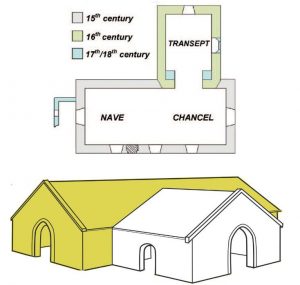

The main body of the church was built in the 1400’s possibly by Mac Swiney Bannagh for the Franciscan Third Order Regular. The Third Order enjoyed an expansion in the west and North West of Ireland in the 1400’s, particularly in Donegal in the second half of this century. By 1500 five Franciscan Third order houses had been founded in Donegal. There is no concrete evidence however to state when exactly it was built and for whom. The original chapel consisted off the nave and the chancel.

The remains of the Church, 15.6m by 5.2m internally, and N transept, 6.6m by 5.15m internally, testify to at least three major building periods. The main body of the church is probably 15th century and the transept a 16th century addition; the S arched transept gable, the window alterations and the W porch are probably works of the 17th/18th centuries. It is possible that some of the windows in the N and S walls are secondary insertions.

Catherine of Alexandria is, according to tradition, a Christian saint and virgin, who was martyred in the early 4th century at the hands of the emperor Maxentius. According to her hagiography, she was both a princess and a noted scholar who became a Christian around the age of 14, converted hundreds of people to Christianity and was martyred around the age of 18.

The Eastern Orthodox Church venerates her as a Great Martyr and celebrates her feast day on 24 or 25 November, depending on the regional tradition. In Catholicism, Catherine is traditionally revered as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers and she is commemorated in the Roman Martyrology on 25 November. Her feast was removed from the General Roman Calendar in 1969, but restored in 2002 as an optional memorial.

The cult of Saint Catherine was spread across the west of Europe up until the 11th century via the Christian Roman Emperors who adopted the tradition. In Ireland the name is believed to have first appeared in the 12th century with the initial colonisation of the southern half of the island by the Anglo-Normans. To this day, the name of Catherine of Alexandria is common throughout Ireland as various holy sites have been dedicated to the cult of St. Catherine.

In Killybegs, the popular story of the introduction of the cult of St. Catherine is that a party of monks were making a voyage on the west coast of Ireland. The boat was caught in a great storm and the monks prayed to St. Catherine “patron saint of sea farers” to protect them and take them safely to shore. They vowed if they reached land they would dedicate a holy well in her honour. The monks arrived safely in Killybegs and dedicated the well to St. Catherine.

The Annals of the Four Masters state that the town of Killybegs was plundered and burned twice in this century.

The first event was in 1513 when Owen O’ Malley, of the infamous pirate clan from western Connaught, pillaged the town and captured many prisoners, at a time when the fighting men of the area were away with O’ Donnell’s army. Brian, the young son of the Mac Sweeny chieftain, and others attacked the O’ Malley’s and rescued the prisoners. The account states that this was through the miracles of God and St. Catherine, whose town they had profaned.

The second time was in 1550 when Rory Ballagh Mac Sweeney who, in retaliation for not receiving the lordship of Tir Bannagh from Manus O’ Donnell, “went to Killybegs, and totally plundered that town”.

These accounts give us a good insight into this period of inter-clan skirmishes, typical in Gaelic Ireland. Church property was not exempt from plunder. With the record stating that the O’ Malleys incurred the wrath of God and St. Catherine, it is possible that the attack also extended to the church.

Another significant event took place in 1588 when ships and crews of the Spanish Armada landed in Killybegs.

The Spanish Armada was a fleet of 130 ships that sailed from Spain in late May 1588, under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidonia, with the purpose of escorting an army from Flanders to invade England. Following its defeat at the naval battle of Gravelines the Armada attempted to return home through the North Atlantic but was driven from its course by violent storms, toward the west coast of Ireland. Up to 24 ships of the Armada were wrecked on the rocky coastline spanning 500 km, from Antrim in the north to Kerry in the south. It is estimated that some 6,000 members of the fleet perished in Ireland or off its coasts.

The Armada ship La Girona docked at Killybegs for repairs. Around 1500 Spaniards waited in Killybegs of which 800 were survivors from two other Armada shipwrecks – La Rata Santa Maria Encoronada and Duquesa Santa Ana. These men may have attended St Catherine’s church during the period they stayed in Killybegs before the subsequent and fatal journey on La Girona.

From 1593 to 1603, the Nine Years War was fought in Ireland, between the Gaelic Lords, mainly of Ulster, and Queen Elizabeth’s forces.

The failure of the Gaelic forces at the Battle of Kinsale on the 3rd of January 1602 and the subsequent Flight of the Earls in 1607, signalled the end of the Gaelic order. Ulster was now open for English conquest and all its lands were forfeit to the crown.

In 1609 an inquisition was held at Lifford to determine the size of church lands in Donegal. With this established, all church lands became the property of the Protestant Church. St Catherine’s became the property of the new Church of Ireland. The second arch and gable was built in this period as well as the blocking up of the main doorway.

The 1641 Rebellion was an attempt by the remaining Irish nobility to regain the lands and power they had lost. In the early days of the rebellion, a fierce battle occurred at Stragar, about four miles from Killybegs. The Irish forces under Turlogh Roe O’Boyle of Kiltoorish, and the sons of the late (and last) Chieftain of Bannagh, Donough McSwyne, were routed by the Crown forces under the Reverend Andrew Knox. There is no record of a second battle, but in 1642, Colonel Mervyn admits that the English forces evacuated Killybegs. The Irish immediately filled the vacuum left by the withdrawal of the English forces. The Franciscan friars from Donegal took advantage of this and settled into the church. A number of these friars were captured in Killybegs by an English ship that came in disguise and succeeded in capturing Father Ultach and Father Fergal Ward. Father Ward was hanged about three months later while Father Ultach was brought to England where he died in prison shortly afterwards.

By 1648 the town was back in the hands of the English forces and the friars had fled again. St. Catherine’s church was again in Protestant control. This troubled period may have damaged the church, as the 1654-56 Civil Survey showed that the church was in repair. The remainder of the seventeenth century in Killybegs was quiet; the turbulence of 1690 seemed to have very little impact in the area.

The gable end was added to the church in the 16th century as the church changed hands from Catholic under the Gaelic order the Protestant Church of Ireland.

The eighteenth century in Killybegs was a much more settled period than the previous century. People took advantage of the peace to develop trade and fishing. The new town of Killybegs was now the main area for development and commerce and only the church remained in the old medieval town

Fortunately there are a number of historical records throughout this century concerning the church. In 1729 the Bishop gave one hundred boards for seating. In 1733 the church is described as in good order, seated and the aisle and altar flagged with stone. A baptismal font was donated to the church in 1717 and is now located in St. John’s Church. Unfortunately its inscription is very difficult to read and only the date is legible. It is the only known surviving furniture from St. Catherine’s Church.

It was decided in a Select Vestry meeting in 1788 to re-slate the roof of the church. The new roof was completed in 1790 under the supervision of James Hamilton and Andrew Nesbitt at a cost of £15. Further work was carried out in 1793 to enlarge the chancel window, which cost £1-10-0. In 1795 the road to the church was improved with a new pipe drain. Two new sash windows were installed on the church at a cost of £1-16-6; it is still possible to see traces of the sash frames in the remaining plasterwork on the church.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Church of Ireland had commenced an impressive church building programme through the Board of First Fruits. Money was secured by the parishioners and in 1825 building began on a new church located in the new town, a much more convenient location than St. Catherine’s. By 1828 the new church was complete and was dedicated by the Bishop on the June 6th.

The baptismal font is the only remaining artefact from the church. It was removed at an unknown date and now resides in St. Johns Church in the town of Killybegs.

After religious worship for over five centuries St Catherine’s Church was now abandoned. Burials continued in the graveyard but the last living link with medieval Killybegs was severed.

St Catherine`s Church today in the 21st century is in a very poor condition. It is the oldest surviving building in Killybegs and a window into over five hundred years of our history.

As the church was largely ignored for the greater part of the 20th century it became mostly forgotten within the memory of the community. A valuable link to the history and heritage of the area was almost lost save for the efforts of the community heritage society.

Efforts to research and preserve the site and surrounding area have resulted in a published history that forms the source material for this project.

The community have also undertaken physical reconstruction work of the church to preserve the remains for future generations.

All work was carried out with the approval of the Heritage Council, Donegal County Council and the National Monuments Service and the active involvement of archaeological consultants.